It is early Sunday evening and on the outskirts of Bridgetown a street preacher can be heard singing the praises of his Lord.

But there is something edgy about David Murray’s demeanour – he is wearing the same yellow T-shirt, shorts and trainers, which dwarf his bony ankles – but he is not the cool “clean” guy I had met only days ago.

At the Stadium Road Bar & Restaurant, a rum shack opposite the crumbling National Stadium, Collis King is living up to his reputation as the great entertainer of West Indian cricket, reeling off rum-soaked anecdotes in the same cavalier fashion he dominated bowlers.

Murray sits beside him at the outdoor table, his anxiety dimmed by several glasses of Mount Gay dark rum and tonic. He is clearly enjoying being close to a man who has shared much of his cricket journey, but little of the hardship.

King is a big guy. He can handle his alcohol. Murray cannot.

He is soon clutching his old teammate’s right hand, gibbering “I love you, man”.

It’s obviously a heartfelt sentiment but after a dozen or so admissions, King gently takes Murray’s hand and repositions it on the bench.

An incomprehensible low-level burble is all Murray can manage for the rest of the night.

Malcolm Marshall described David Murray (above left with the author, middle, and King) as the best, most agile ’keeper he played with, the only one he could rely on to snaffle every half chance off his bowling. Joel Garner said he would trust Murray to keep for his life.

Even Jeffrey Dujon, the man who succeeded him as West Indies custodian, says Murray was a class above him behind the stumps - that he made him look like "Dolly Parton standing up to spin".

But he only played 19 Tests over three years, sandwiched between the venerable Deryck Murray and the flamboyant Dujon.

A lot of the rest of his life has been devoted to marijuana. Even on the cricket pitch and in a maroon cap.

“It was good meditation,” he laughs. “You could concentrate for real. First ball you say: ‘Good luck to everybody’, and then I’m on my own. The stronger it was, the more I would concentrate.”

But it was also, in part, his downfall.

On the West Indies tour of Australia in 1981-82, just two Tests after bagging a West Indies record nine dismissals at Melbourne, he was ousted by Dujon for among many things, failing to attend team meetings and turning up to the Adelaide Test without his gear.

Dujon recalls seeing Murray stoned at the old Camperdown Travelodge: "I said to him "'D', we had a team meeting, and he kept looking at the cars go by and said, 'Yeahhh, you know," He was as high as a kite."

Distraught at being dropped, and with a young family and bourgeoning drug habit to feed, Murray was the kind of easy target SACU board member Ali Bacher knew to throw pots of kruggerrand at.

But when Murray gloved up for the first time in the pariah republic, the enormity of what he’d done – the life ban, the uncertain future – sunk in.

“[Captain] Lawrence Rowe said to me as a joke: ‘You can’t play for the West Indies anymore.’ Only one delivery. It felt bad.” A tear rolled down his cheek.

When he returned to Barbados, he says he was ostracised by the cricket fraternity and broader society. "It was fucked up,” he says. “They say things like ‘he sold his birthright’. You can’t play on certain pastures. They still do.” He had money to burn - US$100,000 of it - and burn it he did, on women, fast cars and cocaine.

"I fucked up," he says. "I still smoke,” he adds, “but not like before. I just need a little smoke and I’m high. You just got to smell it now. I’m cool, my brother.”

He also deals to what he calls the "chosen few", wandering the tourist beaches near Bridgetown before returning to a family home in Station Hill, four doors down from an old prison, where he lives with two aunties.

The following afternoon I call Murray to see how he is. We hatch a plan to meet at Pirate's Cove beachside bar in central Bridgetown then drive to see fellow rebel Alvin Greenidge at the Barbados Defence Force training ground.

Pirate's Cove is a thatched palm-leaf and cane affair gazing across the Caribbean Sea – a textbook tourist setup with hammocks and cheap Carib beer: the perfect spot for Murray to deal to his “chosen few”.

Watching Murray discreetly work the small crowd of European and local buyers, it’s clear he is on familiar sands. It is also clear he is not clean. He shoots glances at imagined enemies and when he spots me, blurts out a desire to meet Mark Taylor because he is a “beautiful person who stopped his score on 334 out of respect for Don Bradman”. It is the last coherent sentence he will make all night.

I’d planned to ask him about comments he reportedly made in South Africa claiming apartheid was not so bad, comments Aboriginal activist Charlie Perkins said should have precluded him from being allowed back into Australia.

But after drinking half a glass of red wine, he is too wasted to respond to anyone. We will not be seeing Alvin Greenidge this evening.

Chefette is Barbados’ homegrown “broasted” chicken chain. Locals consider it superior to KFC which has failed to penetrate the island. It is dinner time and it seems a reasonable bet that Murray will be happy to eat at one of their purple and gold-liveried restaurants throughout the capital. I can’t leave him at the bar in his current condition.

“What would you like, Dave?”

He looks at me like I’ve flushed his stash down the toilet.

“David!” he grunts, suddenly hostile to the abridged version of his name.

Chefette’s clientele is mainly families and groups of flirting teenagers; that their country’s greatest wicketkeeper is lurching among them, stoned and incoherent, is either too familiar a sight or simply not entertaining enough to be of concern.

Murray scrapes together greens from the salad bar to take away.

In the hire car, I suggest driving him back to Station Hill but he doesn’t want to go home. There’s fellow rebel Emmerson Trotman’s bar in St Lawrence Gap, but that holds no appeal either. We drive up and down Highway Seven, avoiding effluent spewing from manholes – the south coast was experiencing a huge sewage problem at the time – and tolerating each other’s company.

Eventually, he convinces me to let him out near the gaudy entrance to St Lawrence Gap. It is 9pm. Despite fears for his safety, I stick B$50 in his hand and wish him well. He has played the game. Another foreign media representative seen off. One last reprimand for calling him “Dave” again, and he shuffles into the night.

At the Barbados Legends Museum (above), opposite Kensington Oval, homage is paid to the nation’s cricketers. The tiny island has produced more test representatives per square kilometre than any other country. The museum's downstairs layout is divided into “legends”: the Bajans who've played for the West Indies; and “icons”: local greats of the game such as Garfield Sobers, Frank Worrell and Murray's father Everton Weekes.

Portraits of the living “legends”, photographed in suit and tie, adorn the walls, alongside a potted history of their achievements. Geoffrey Greenidge, the last white man to play for the West Indies is there, so is Murray's buddy King.

They appeared in 14 tests between them. Murray played five more, but there is no portrait of him. Perhaps he was dealing at Accra Beach the day the pictures were taken. Perhaps he doesn't own a suit. More likely he never quite fitted the Bajan cricket establishment's mould.

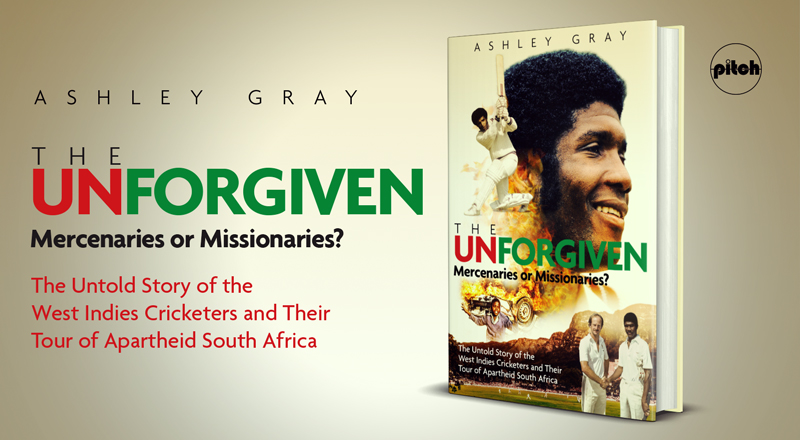

Click here or on the pic below to purchase a copy of Ashley Gray's brilliant book, The Unforgiven.

Join the cricket network to promote your business and expertise. Make it easy for people to search and find the people and services they need through people they know and trust.

Join the network