“He cheated. He did the wrong thing - why did he do the wrong thing?”

I have known seven-year-old Charlie McQuire for just over a year now - having first met his father, Anthony, who is a specialist mental skills coach at the Melbourne University Cricket Club. And that is how Charlie surmised the actions of his then hero, David Warner, when his role in the Cape-Town ball tampering fiasco became apparent.

What is striking about Charlie, who comes to all of our club matches, is his undying passion for sport, and more specifically, cricket. In an era where sport has come to be seen as a commodity to be bought and sold by advertisers, and where cricket in particular in Australia, has recently been rocked by player pay disputes, the ball tampering scandal, and the most recent television rights deal,it’s easy to see how the cricket can get lost. It’s easy to see why young people might miss the point - and fall in love with the bright lights, Kids’ (or should that be KidZ) Zones, and various paraphernalia which inevitably accompanies the game at the highest level. Cricket, in a professional setting is losing its purity, and has undergone significant change and trauma, and attitudes seem to be changing amongst those who play it. After all, if not playing for big bucks and in front of big crowds, why play at all?

Stories like Charlie’s are both refreshing and fortifying; the unfettered passion which pervades his sporting pursuits is a pertinent reminder that when it comes to cricket at the grass roots, the game itself trumps all.

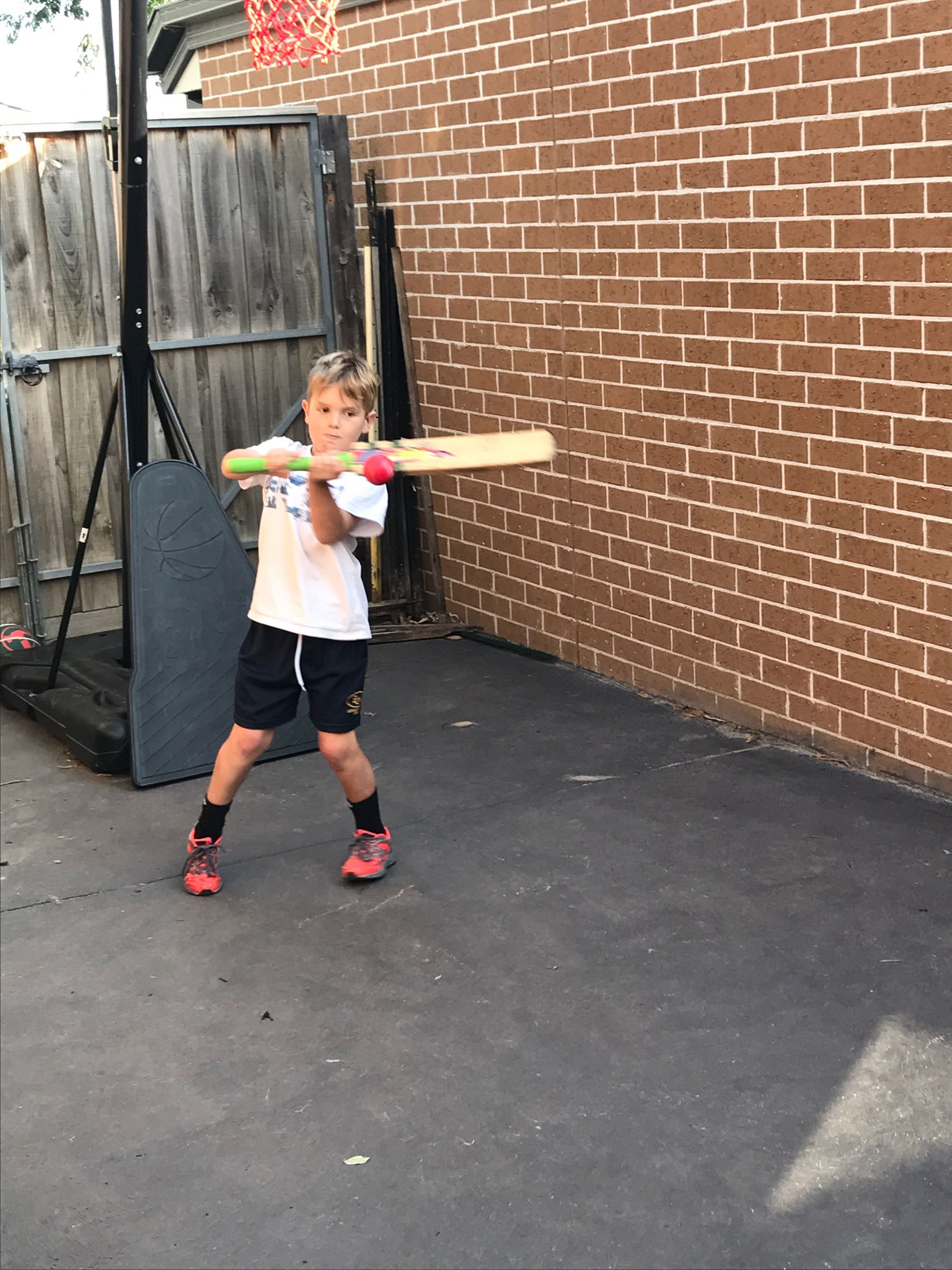

I visited the Mcquire household a few months back for a post season review with Anthony, and after chatting cricket for a while,it was time to play. Charlie hurries to retrieve his two favourite bats, a pair of gloves and helmet, before taking guard; readying himself for my medium-pacers. He sets an imaginary field, “the tree and the window are out, over the roof is six.”

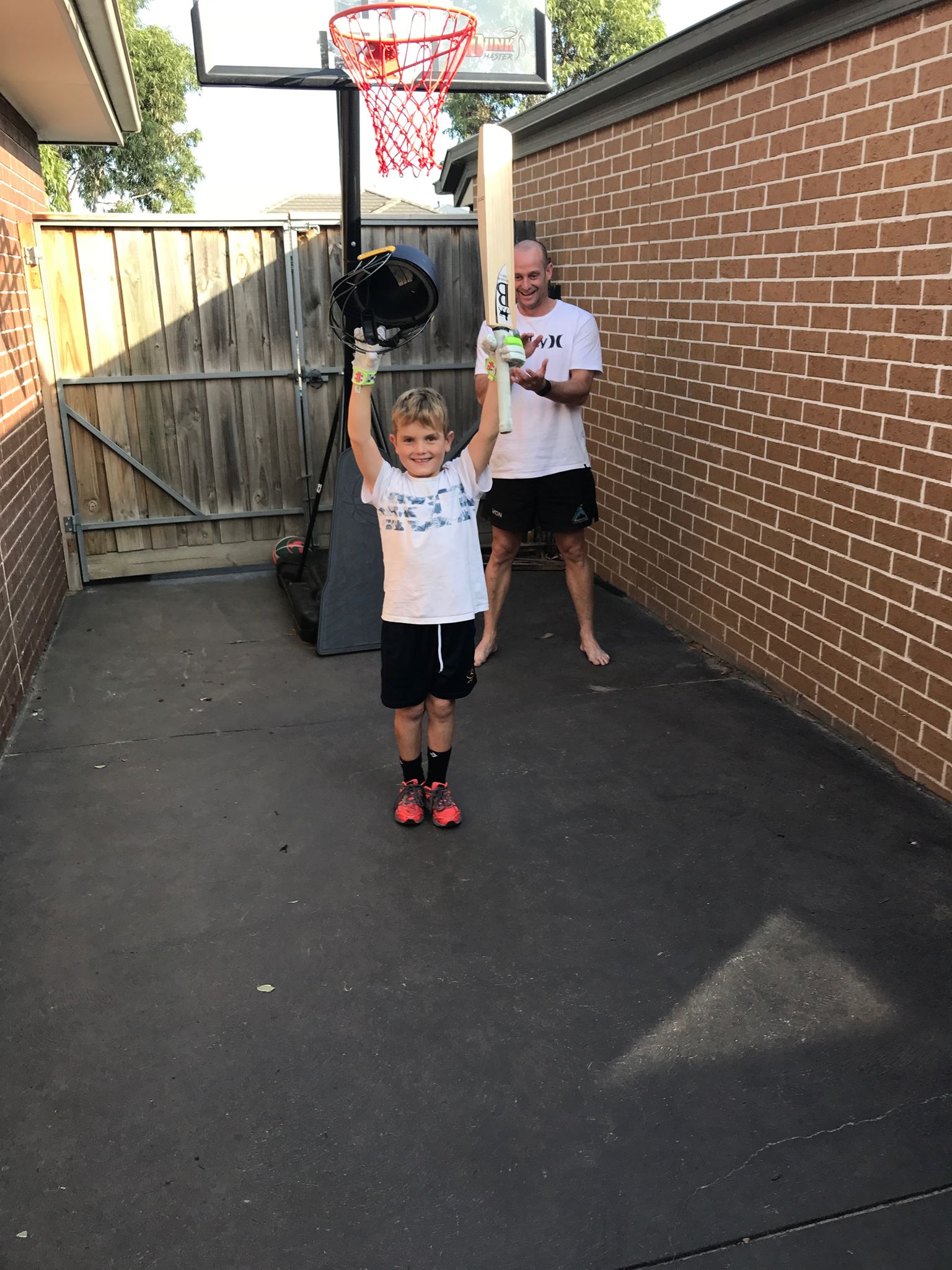

Anthony takes his place as wicket-keeper, playfully chirping his son. It quickly becomes apparent that anything I dish up is fodder for the youngster, who deposits two of my first six deliveries over the aforementioned roof. With a technique shaped by a desire to hit the ball hard and exude maximum enjoyment, not to mirror the proverbial cricketing ‘textbook’, Charlie whips straight balls through mid-wicket, and takes a liking to lofting anything wide over an imaginary cover fieldsman. Before long, he proudly proclaims he has made his way to 96, just four runs shy of yet another backyard century.

The next ball is clubbed through the leg side for two, 98. Then he plays and misses outside his off stump; regardless of age or motivation, the ‘nervous nineties’ afflict any batsman. Nevertheless, he calmly plays the next ball down the ground, and is quick to raise his arms in a well-rehearsed celebration routine.

Another hundred, well batted Charlie.

Charlie can’t explain why he loves playing cricket; it’s just something he enjoys doing. His father tells me “it’s a natural affection.”

Charlie hasn’t fallen for the advertising, or the carnival-like attraction of a night at the Big Bash League. Nor does he know or care about the potential to make a squillion from playing the game, or the status that could come with it.

Test cricket is his favourite format, and he cried when David Warner gave his post sandpaper press conference. Raw passion and pure innocence define Charlie’s relationship with cricket, and these intrinsic traits are what make sport, at its most fundamental level, so special.

Esteemed cricket writer and broadcaster, Mike Coward, shares concerns about the game’s direction. For Coward, who has seen cricket transition through World Series, and now the growth of the shorter formats of the game, he is not sure how much revolution he can take.

As for the English Cricket Board’s most recent proposal for 100 ball cricket, well that leaves him stumped. Indeed, money talks but at times it seems to talk louder than the 140 year history of Test Match cricket. He describes twenty-twenty cricket as “unwriteable”, and includes One Day cricket in the conversation when suggesting short form cricket is not particularly memorable, with World Cup matches being the only ones he tends to remember, though he called over 300 ODI’s.

So, for a man whose value in a game is “that it can be recalled”, he finds himself a touch disillusioned with the state of cricket at the top level.

Happily, though, Mike’s work as an ambassador for the Bradman Foundation and a director of the LBW Trust - Learning for a Better World, which utilises the cricket community to promote education and opportunity in the developing world - continually reassures him of the enduring strength and appeal of cricket, as well as the passion of its people.

Regarding the Trust, he mentions the importance of cricket and cricketers broadening their reach and using their impact for good, espousing values of humilty, courage and skill. He cites former New South Wales representative, Ryan Carters, as someone who truly understood their role as custodian of the game when playing and now someone who is having a positive impact more broadly as a member of the LBW Trust.

I shared an hour and a half in the car with Mike on the way back from Bowral at the end of last season, where the Bradman Foundation held their Chairman’s XI match and luncheon to round out another Summer. Though the weather was gloomy and largely unfit for cricket, a group of us, comprised of Foundation members, Board directors and general cricket tragics assembled at the Bradman Oval to embrace the spirit of cricket.

I opened the batting alongside Mark Faraday, executive lawyer at Henry William Lawyers in Sydney, was captained by Andrew Wildblood, executive Director of Telstra Businesss and Enterprise, and fielded next to ex-international cricket umpire, Simon Taufel.

While the match was not particualrly close, and we spent large parts of it with hands in pockets, bent double against the cold, it highlighted cricket’s unique ability to bring together a cross-section of people with a shared love of the game.

After the match, we moved into the Bradman Museum for lunch, where Mike Coward interviewed the last remaining member of the famous Australian ‘Invinvicibles’ team, Neil Harvey. A voice of distinction in cricketing circles, Harvey spoke fondly of his experiences as a cricketer - experiences for which he, like his contemporaries, was not paid. He recalled that he did not even have a bat of his own during his first test matches, but he did harbour an unwavering passion for the game and its impact.

Travelling to England in 1948, he saw the galvansing effect of cricket in post war England, as the Ashes provided a distraction from the pain and struggle for the locals.

This is the power of cricket, and the wonder that must be retained, for as much as cricket is a game, when played in the right spirit, it can be so much more.

While the game has endured a tumultuous period in the professional environment and there is not necessarily an end in sight, Mike Coward highlighted that there has been some good to come from it: that being the re-affirmation of the importance of the spirit of cricket.

If the customs and tradition of the game were not respected broadly in the cricket community, incidents such as the most recent ball tampering debacle, would pass largely unpunished. That the guilty trio have all endured a lengthy period on the sidelines highlights the value we, as a cricketing public, place on respecting the game.

Bearing this in mind, it is easy to see that the cricket is in good hands, and can look forward to a prosperous future. That it can, in the face of challenge and change, inspire a life’s work of cricket writing and broadcasting, exude passionate remembrance from a former test legend, and foster heartfelt joy for a seven-year-old who is yet to play his first competitive match, is testament to its multi-dimensional appeal.

As for Charlie’s innocent and troubled wonderings, may he never find a viable answer.

Join the cricket network to promote your business and expertise. Make it easy for people to search and find the people and services they need through people they know and trust.

Join the network